Pop-pop-pop-pop!! I was staying in a guest house less than two blocks away from Plaza Italia, the epicenter of political protests that happen most evenings in Santiago, Chile. Sirens had been screaming up and down the avenue outside my window for more than an hour when the first four shots rang out. The screams of demonstrators and rocks bounding off police armored vehicles, punctuated by occasional gunfire, continued until 10 p.m. Then, as quickly as it had begun, the protest dissolved and quiet descended. I’d put off my visit to Santiago till the last minute. During my cruise to Antarctica I’d met two couples who had visited the city over the previous couple of weeks. Both had been robbed. I could find little current news coverage that answered the question, “is Santiago safe to visit at this time.” In the end, since I had to fly through Santiago in order to visit Easter Island, I decided to take my chances.

Over the next five days I explored the Chilean capital on foot. My first stop was the boarded up Metro station at Plaza Italia, a couple of blocks from my guest house. I was reading slogans painted across the graffiti-plastered entrance when a 23-year old nurse on a bicycle stopped and began explaining what the protests were all about. On October 19, 2019, residents of Santiago, Chile, took to the streets to protest a hike in subway fares. Long considered to have the best economy in South America, that wealth had not trickled down to the common people, a majority of whom were poor and had little access to even basic services.

The increase in public transportation fares was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Years of festering rage boiled over and people took to the streets. Police fought back by firing tear gas canisters and pellet guns. Echoing the era under the brutal dictator Pinochet, who ruled Chile from 1973-1990, police aimed their pellet guns directly at the eyes of demonstrators and spectators alike. More than 200 people were completely or partially blinded before the government banned the use of these guns in November of 2019.

I crossed the avenue to a large, graffiti-covered monument where demonstrators were perched. They agreed to be photographed, but only after explaining why they are demonstrating and what they are demanding. They claimed that many poorer Chileans do not even have running water in their homes, despite Chile being a water-rich country. I later learned that water access and use in Chile is regulated by the 1981 Water Code, which was enacted by the military regime with strongly pro-business bias. The code allowed water to be privatized.

As a result, high percentage of water ownership was concentrated in the electric, mining, and agro-business export sectors. Rates subsequently increased to the point where many in lower socioeconomic classes could no longer afford it, despite subsidies offered by the government. The young protestors also insisted that the flourishing mining industry uses massive amounts of water, but all mining revenues go to the rich owners.

Chile also passed a sweeping fisheries law in 2012. Not only did it cut quotas in half from one day to the next, the quotas weren’t divided evenly. Only 40% of the country’s total catch was awarded to Chile’s 92,000 artisanal fishermen. The remaining 60% was awarded to the industrial fleet, which is owned by just seven wealthy families. Inequitable distribution of quotas, declining level of fish species, and increasing hauls by the large industrial operations have made it impossible for many independent fishing boats to stay in business.

Every Chilean I spoke to insisted that the demonstrations will not stop until the government meets their demands. They want the constitution (which was adopted during the Pinochet dictatorship) to be rewritten, the current government to resign, an increase in the minimum wage, better health care, better pensions, and an improved educational system. The government, while refusing to step down so far, has agreed to hold a referendum in April to determine if the constitution should be rewritten.

However, no one seems to know what will happen if the referendum is successful. To date, the demonstrators have not formed an organization, created a platform, or provided an official list of their demands. They have not offered up candidates and refuse to be involved in the process of rewriting the constitution. Without organization and involvement, the process seems doomed to fail.

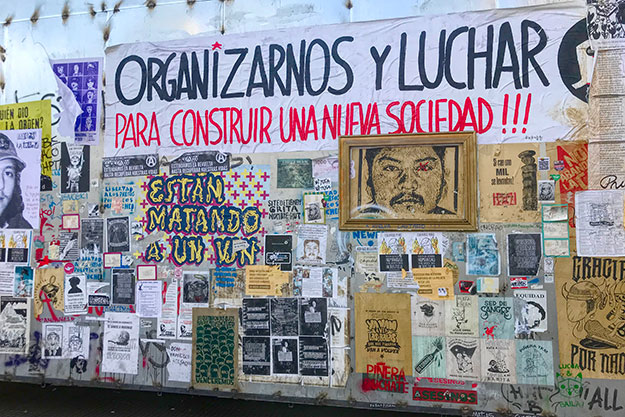

Some parts of the city look like a war zone. Prior to the eruption of demonstrations, Plaza Italia was one of the most beautiful areas of the city. Today the monuments and elegant buildings that line the broad avenues are covered in graffiti. Almost every business has closed and the few that remain are boarded up with plywood. Plaza Italia, once a flower-filled park, is now a dusty, litter-strewn circle without a single remaining bush or flower. Yet walk ten blocks in any direction and life goes on as usual. While I opted to stay near Plaza Italia in order to be close to the action, there are many places to stay in Santiago where there are few signs of the protests. People enjoy lunch at sidewalk cafes and businesses are open as normal. In Plaza de Armas, the historic center of the city, despite a heavy police presence the park remains lush and relatively peaceful. The most stirring site in the city was the block-long Centro Gabriela Mistral Cultural Center. Its exterior walls are plastered with works of art symbolizing the struggle, including a line of blood-spattered shirts from victims of police brutality.

Although I found the energy of Santiago unsettling at times, I never felt threatened, or felt the need to get out of an area. Locals, however, seemed more alarmed for my safety than I was. At least a half-dozen times, complete strangers approached and warned me to watch my purse or my camera. While walking back from the fruit and vegetable market, one man was more forceful. “You should not be here. It’s too dangerous. On the other side of the river it is safe for you but not on this side.” Never in all my years of traveling have I had so many people warn me to be careful in a city.

On my final evening in Santiago, I was having dinner at the only restaurant that remains open in the Plaza Italia neighborhood. My waiter (oddly enough, named Santiago), explained the meaning of the graffiti slogans painted across the facade of the building. Although I speak fairly fluent Spanish, slogans are some of the hardest to translate because they include a lot of slang. The words “Paco” and “Yata” are both slang for cops. The acronym ACAB stands for “All Cops are Bastards” – why it is in English he couldn’t explain. The designation “1312” also refers to the ACAB acronym; A is the first letter of the alphabet, C is the third letter, etc. A good deal of the graffiti has to do with eyes. Eyeballs with blood dripping from them. Eyes with giant X’s painted over them in red. Faces with a patch over one eye. And perhaps the most heart wrenching slogan of all, “nos quieren ciegos.” They want us blind.

From my sidewalk table that evening, I had a birds-eye view of the demonstration as it began. Students and workers streamed in from all directions. The police rolled up in an ominous dark green SWAT van, with cages around the windows, cow-catchers in front of the wheels, and water cannons mounted on the roof. A second smaller vehicle stood by at the curb while the van moved forward and backward, spraying the rock-throwing protestors with jets of high-powered water. I paid my bill as my server was hurriedly stacking up chairs and carrying tables inside. Gradually I crept closer to the police vehicles as I recorded the action on video.

Suddenly, the rear door of the smaller armored vehicle swung open and a gun-wielding cop wearing a black knitted mask popped out. He aimed the weapon at protestors and fired several times. Pop, pop. It was the same sound I’d heard on my first night in Santiago. The government may have ordered the police to stop using pellet guns, but my video clearly shows that the order is not being heeded. To date, nearly 300 people have lost the vision in at least one eye due to police firing them directly at the eyes of protestors. “Nos quieren ciegos,” it seems, is the truth.

When the pellet gun came out I decided it would be best to retreat. I walked across the street to my guest house and spent the rest of the evening listening to the sounds of the fighting. Once again, by 10 p.m., everything was peaceful. As to the question, is Santiago safe to visit at present, if pressed for an opinion, I might advise waiting until the political situation has stabilized and at least some of the damage has been repaired. On the other hand, I found Chileans to be warm and welcoming and completely open to sharing their opinions. My visit was fascinating and educational.

Author’s note: The protests are not likely to stop any time soon, however they are easily avoided. Mostly they occur on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings, beginning around 5 p.m. Friday is always the biggest protest of the week, and most of the action occurs around Plaza Italia. So, is Santiago safe? Yes, if you stay away from the protests and use common sense. At a minimum, do not flash money round, don’t wear any jewelry, and stay in well-populated areas.

This is a sad story but one that has been fairly common in South America. Seems like a lost cause if the two sides can’t come together and start talking. It’s been proven that violence doesn’t work. Ghandi was a good example of that. There is disparity between the rich and poor all over the world and we have to stand up to those who allow it to happen. But violence isn’t the way. I hate to think that Chili could become another Venezuela or suffer through what Argentina did in the ’70’s. So sad because any Chilean I have ever met was so open and proud of their beautiful country.

Hi Betty: Yes, I am worried about the situation as well, and Chile is only one of many such uprisings around the globe right now. We live in an upsetting world right now.

An extremely fascinating, well-written article and your photos and video are compelling and thought provoking. Santiago has been on my radar only because of the fact that certain South America cruises either begin or end in the relatively nearby coastal city of Valparaiso, and associated flights would be into/or out of Santiago. However, I was totally unaware of the situation in Santiago. Thanks to your ability to engage locals in conversations about the situation, it has shed a light on what is at the root of these confrontations, and I think it took a fair bit of courage to stay in the midst of it! Love your photos! Thanks!

Thanks so much for your comment Sylvia. Glad you found it interesting.

What a fascinating article. Thank you for sharing. My husband and I spent most of last year in Latin America but did not go to Santiago.

Hi Linda: I wish I could have visited before all the destruction. I can see the city has great bones, but it will be a while before it recovers.

This saddens my heart. We were there for a week in September and Plaza Italia was the hub for our daily excursions. Even then we were approached by one many who was very concerned that we were travelling on public transport with our luggage and warned us (via google translate) to be wary of thieves. Thank you for taking the risk to record this and share.

I also found the situation quite sad Esther. I really hope they find a way to effect the changes they desire without destroying the city much more.

Enjoyed reading this account. it was very informative about the ongoing situation in Chile.

Thanks for this. This is a over good account of situation in Santiago. The demonstrations are, for the most part, avoidable. The most practical advise being avoid Plaza Italia from 5 on and especially on Fridays.

(On minor correction. The 200 blinded, and later in article 300 who lost there vision is a much quoted exaggeration. While, and let me stress, even one blinding is one to many, the local human rights organization are citing 33 blinded in one or both eyes).

Iain – a Santiago expat resident

Glad yuu enjoyed it Julia