Had I only stayed one day in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county, as planned, I would have left believing that the meandering rivers, lush orchards, and bucolic villages were pretty, but otherwise uninteresting. Fortunately, one day turned into five and this region, rife with legends that have been handed down from father to son and grandparents to grandchildren for generations, revealed its secrets to me like a flower blossoming from a tight bud.

My adventure began in Mátészalka, the second largest city in the county and home to the Szatmari Museum. After a leisurely walk around the grounds to view the museum’s impressive collection of traditional wooden carriages, coaches, and sleds, my hostess Zsuzsa Méhész whisked me off to lunch so that I could recover from the five-hour sweltering ride on the rickety old train that had carried me from Debrecen.

An hour later, full of Hungarian pickles and vegetable soup, I was more than ready for round two, The Route of Medieval Churches. The Great Hungarian Plain, situated on the eastern frontier of Western Christianity, was once littered with churches. Though most were destroyed by the Mongol invasions of the 15th century, those that remain are concentrated in the Szatmár region, which was largely spared because mounted armies could not easily navigate marshlands created by rivers that regularly flooded the area.

The late Romanesque style church in Csaroda is the star of this collection. Between the end of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th centuries the Csarnavodai family, which owned the village at that time, built the church as their private place of worship. The small square sanctuary, larger rectangular nave, and needle-like spire that soars above the trees are remarkably well preserved, but it is the interior that truly astounds. When Calvinists took over the church in 1595, they covered the existing Medieval frescoes on the walls with a layer of lime and painted it with heart-shaped floral motifs. The earlier frescoes, preserved by the overlying plaster, were discovered during restorations undertaken in the 17th and 18th centuries. Today, partially uncovered frescoes of the apostles, Mother Mary, and baby Jesus share the walls with the later Calvinist floral designs, which are rare in their own right.

Though built after the middle ages, the 18th century Calvinist Church (Reformatos Templom) and bell tower in Tákos was no less impressive. The rustic exterior, constructed of sticks that have been set in a wooden frame and covered on both sides with clay and mud, did not prepare me for the jaw-dropping interior. Its coffered wooden ceiling consists of 58 panels painted with floral motifs, each unique because guild regulations of the day required that each panel bear a different design. The hexagonal pulpit, which also bears floral designs, sits on a rock that symbolizes the strong foundation of the church. As we entered, an elderly female volunteer creaked to standing position and spoke for a quarter-hour about the history of the church. Zsuzsa translated as best she could, shaking her head in amazement at the matron’s knowledge, which she shares eagerly and without compensation every day of the year.

The Route of Medieval Churches includes 30 churches, 20 in Hungary’s Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county and ten in neighboring Satu Mare county, just over the border in the area of Romania known as Transylvania, which was part of Hungary until the borders were redrawn after World War II. More than just architectural sites of historical import, for many these churches are a spiritual experience, a pilgrimage even, especially in the case of the Greek Catholic church in Máriapócs, where in 1696 the Madonna icon that hangs above the altar is said to have shed real tears. It was the first, but definitely not the last of the legends of Szatmár that would be revealed during my stay.

Stories about dragons are among the more titillating legends. One such creature is said to have blocked Hungarian troops on their way to engage invading Turks. Their leader, Gábor Báthory, was asked if he dared fight it. He replied, “Mérek (I dare).” The town that later sprung up on the site was named Merk in honor of his bravery. Further south, on the spot where he wounded it in the shoulder, the village of Vállaj was established. Finally, he killed the dragon and threw its carcass in a bed of nettles, which later became the village of Csanálos. Gábor seems to have come by his dragon fighting abilities naturally; in the year 900 his ancestor, the warrior Vitus, slew a dragon that lived in the swamps and terrorized the countryside. Grateful villagers named him Báthory, from the Hungarian “bátor,” which means brave. Some say these are just legends, but there are those who believe that dragons still roam Szatmár. At the end of the 19th century, a man from the marshes claimed to have shot at a red-crested dragon. He missed and it disappeared without a trace.

Witches also figure strongly in Szatmár folklore, and not the fairy-tale or book kind. In the 300-year period between 1450 and 1750, more than 7,000 witch trials were conducted in eastern Europe and an estimated 2,000 victims put to death. Szatmár County was not exempt from the madness. In 1728-29, the largest witch hunt in Hungary’s history sentenced two women from the Szatmári village of Tuykod to be burned alive. On the testimony of eighteen witnesses in the witchcraft trial of 1745, Pila Rekettye and Anna Varga were tortured and then burned alive in the village of Nagykároly. At the height of the hysteria spiritualists and healers were also being targeted and as a result few people were willing to be trained as doctors or nurses. Realizing that public health was being negatively affected, in 1756 Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, who was also the queen of Hungary, demanded that all future witchcraft cases be forwarded to her court for confirmation. By 1777, witch trials were a thing of the past.

Despite all odds, the natural healing arts survived the purges and I was excited to learn that one of Hungary’s most respected herbalists, Bela Makay, lived nearby in Túristvándi. Reed thin, with a ruddy complexion topped by wavy gray hair, Makay met us at his garden gate and led us to a picnic table beneath a wide shade tree. Chattering non-stop in Hungarian, he poured what appeared to be ice tea from a tall yellow pitcher into small Dixie cups. “This is his famous tonic for purifying the blood and ridding the body of toxins,” Zsuzsa explained. “It’s a secret recipe, made from roots, leaves, and flowers he gathers in the forest.” I sloshed a bit around in my mouth; it was slightly bitter but refreshing. I followed it with a second cup and asked her to inquire whether it might help my aching joints. He shook his head and disappeared into the house, emerging a few moments later with a small ceramic jar of a foul smelling ointment. Turning again to Zsuzsa, he explained that it must be applied to the affected area twice a day, without fail, for two weeks. After that, he guaranteed the pain would be gone. “It’s made from pig lard,” she added.

Wilted from the late afternoon heat, we headed for the nearby river, where we toured the 18th century wooden mill that is still in operation. I dangled my feet in the cool water and watched the mill’s three water wheels rotate lazily in the current as I rubbed Bela’s ointment into my left shoulder and neck. It did seem to help but it was the first and last time I used it. I just couldn’t tolerate the odor or the thought of smearing my body with pig fat. For all I know, that small white jar may still be in the refrigerator of my guesthouse.

We took a rest from touring the next day, packed up the car with an enormous picnic basket, and headed for the River Túr, at the point where it empties into the Tisza River. I was tempted to swim across the Tisza just to set foot on Ukranian soil, but decided a few steps on a sandy beach did not count as a visit to the Ukraine. Instead, I basked in the afternoon sun; stood beneath water cascading off the Túr spillway, allowing it to pommel my sore shoulders; and gorged on generous slices of watermelon and ripe purple Nem tudom plums that burst open juicily and melted in my mouth.

By the following morning I was rested and eager to learn more about Szatmár’s Way of the Legends. Our first stop was Penyige, where retired teacher Margit Kormany has spent a lifetime collecting thousands of artifacts that document the culture of her village and the Szatmár region at large. It was a sweltering day, with temperatures topping 100 degrees, but Margit was happy to give us a tour of her old school, long since converted to a museum. Ancient farm implements hung in rows on the walls and old black and white photos provided a glimpse into 19th and 20th century Penyige. Hand-thrown terracotta jugs, kitchen implements and old bottles stood in military formation on shelves surrounding her old classroom, still furnished with miniature chairs. The oldest item in her collection, a 100-year old, thigh-high wooden mortar and pestle used for grinding salt, stood in one corner.

Margit recognized her passion for collecting at an early age. Her parents died young and she was raised by relatives who regularly took her to museums. During her University years, she visited an archeological dig and was mesmerized. In that instant, she knew that someday she would have a museum. Of all the items on display, the most interesting is a wall of drawings done by her students over the years, commemorating nine local girls who drowned when their boat, which was carrying them to school, capsized. The incident happened prior to Margit’s tenure and by the time she arrived in 1956 the locals had begun to forget about the tragedy. Feeling strongly that these young girls should be remembered and honored, she forced the town’s mayor and local priest to clean up their graves and wrote down songs and poems that had been written about the sad day. Margit sang one for us that afternoon. Clasping her hands together, she gazed vacantly into the distance as the sad ballad spilled from her lips in crystal soprano tones. We were silent for a long moment after the last note had faded, until Zsuzsa finally broke the spell. ” The village has nine innocent souls, but now I am certain that Margit is the guardian angel of Penyige.”

Since souls seemed to be the theme of the day we climbed back into the car and headed for the cemetery at Szatmárcseke, where all the headstones are carved from wooden boats. No one knows for sure how this tradition developed, though the fact that the graveyard is built on the highest piece of ground in the area provides a clue. Before the rivers were channeled in the 19th century, the lowlands were swampy at the best of times and flooded seasonally. The most popular theory is that bodies were floated to the cemetery on small wooden boats, which were then carved on site and stood upright at the head of the grave. Most of the older gravestones have only a hint of a face but in recent years woodcarvers have begun producing more realistic likenesses of the deceased. Today the tradition is considered so important that each resident chooses a tree tree to be cut down upon his or her death and engages a woodcarver, to whom they give specific instructions regarding the design.

I walked among the mute sentinels, reading verses memorializing long lives and happy marriages. Some were old and weathered, promising splinters for those foolish enough to touch, while others, sleek and black, were reminiscent of the mysterious Easter Island moai. Here and there visitors had adorned the boat-stones with wreaths of dried flowers or wrapped them in silk streamers. But amidst the differences I notices one common trait: each headstone was tilted slightly forward. Zsuzsa stood next to one of the markers and leaned forward ever so slightly, mimicking its angle. Within seconds, she was forced to take a step forward to keep her balance. “Carvers do this intentionally, as it symbolizes that there is still one more step to take after death.”

It was time for my next step as well. Romania was calling but it felt as if I’d only scratched the surface of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county. I hadn’t visited the haunted castle at Jánkmajtis or delved into the stories about bells on sunken monasteries that still toll once each seven years. I hadn’t smelled the wild-roses of Papos, said to be the souls of praying monks and nuns that were turned into flowers rather than endure capture by Mongols. And I’d had time to visit only two of the area’s 20 historic churches. Still, I will forever be grateful that my one day stay became five, for it allowed me to tap into the true essence of this fascinating, unknown corner of Hungary, which is anything but uninteresting.

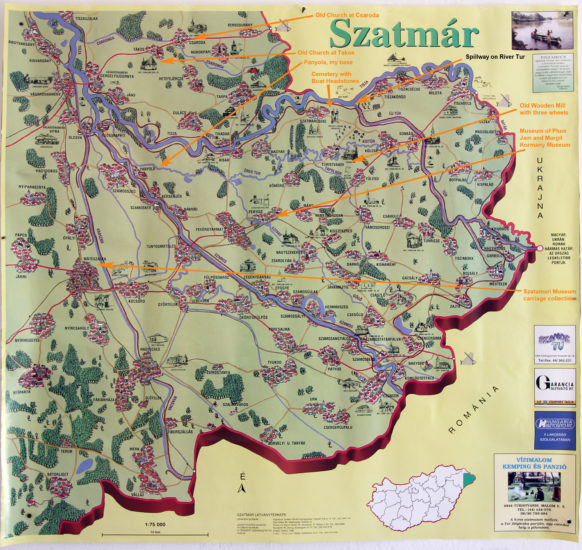

The following map shows the sites I visited, indicated in orange.

For more information about Panyola and assistance with arranging a visit, please feel free to email Zsuzsa Méhész at [email protected] or leave a message on the Facebook Page for her new guest house.

Disclosure: I was a guest of Zsuzsa Méhész and Ambrus Barabas during my stay in Panyola, Hungary. However, the receipt and acceptance of complimentary items or services will never influence the content, topics, or posts in this blog. I write the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

My maternal grandfather was born there. He came to America in 1913 at the age of 16. My family has very little information about his life there. Your blog helped me get a picture of life there. Thank you for that. I’ve always been intrigued to find out more information about the area and people there. I know my family surnames from that area are Kiss and Popp. I hope one day to visit there and learn about my families background.

Hi PD: Thank you SO much fr taking the time to leave a comment. Unlike most blogs, I write stories rather than lists of top ten places to visit. My content doesn’t get ranked highly on Google because they prefer the crap…so it means a lot to me when the stories I write are helpful or interesting to people. I hope you are able to visit one day. It is a bucolic but interesting part of the world that few people see.

Wow! I had no idea this place existed even though I have been in Hungary for over a year now, waiting out the pandemic. I hope to visit it before we leave. Thank you for sharing it.

Hi Linda: I hope you get to visit Szatmar county. It doesn’t offer magnificent tourist sites, but it does offer a true glimpse into rural Hungarian life. Additionally, the Mongols bypassed the area because much of it was flat grassland or swamp and they saw no value in it. Thus, it is home to some quite historic and culturally significant wooden churches.

I learned so much from your story.

Even though I was borne in Satu-Mare I have never heard about those stories.

It was nice to revisit the beautiful,peaceful place that I still recall so foundly in my heart where I was so lucky to have the best childhood one could ask for.

Hi Tunda: Thanks so much for your comment. Happy I could bring back such good childhood memories for you.

Dear Barbara, thank you very much for telling that beautiful story about the east of Hungary. I have been visititing Eastern Hungary for years, I\’ve even been to Szátmarnémeti (Satu Mare), but I only passed the Szátmar region and it was a big mistake, it appears. So now I\’m going to fix it and visit Szátmar, both parts – this remaining in Hungary and that passed to Romania. I feel joy prior to visiting the mill, the cemetery, the churches, eating szátmari palacsinta (pancakes with dried plums, orange peel and cinnamon sauce) and… drinking traditional szatmári szilvapálinka 🙂

Thanks again, all the best for You!

Thank you SO much for your comment Maciej! I hope you like Szatmar and Eastern Hungary as much as I do.

My Great Grandfather, Jon Roth, came from a village called Erendred/andrid and left before the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire, is it possible that Szatmar has census records or any historical data of Jewish Families that lived in Szatmar pre-WW1?

Hi Jonathan. Unfortunately, I just don’t know.

Inspirational article–my husband’s family — actually his father — was born in Szatmarcseke. All his paternal ancestors are from there: Szucs, Fabian & Varga. Why we haven’t gone there is beyond me, but after reading this–I am aiming for 2018!

Thank you Kathy. I’m so glad my story has inspired you to visit Szatmar. I find it a bucolic but still fascinating part of Hungary, and the people are just lovely. Totally unspoiled by tourism.

Anybody know much history of Nyirderzs? My great great great grandparents are from there.

Hi Barbara, I am from the Szatmár region, but live now in another country for years now.

I am always grateful when we have a chance to spend time in Szatmár and use all school breaks to send my son there so as he can learn the humanity and wisdom of that region.

Thank you for your article! Thank you for discovering and sharing those values and hidden wonders! It touched me and made me proud once again of my home land.

I wish you all the best for all of your travels, wherever you may roam!

Thank you so much AHB, especially for taking the time to leave a comment. I really appreciate knowing that people enjoy what I write, and I’m so glad I could bring back such wonderful memories for you.

I came across your article on Pinterest and to tell you the truth even I – a Hungarian living in Hungary with parents coming from Szatmár- found it informative and interesting. Thank you for that. What I missed is mentioning that the saints on frescos in Csaroda are called smiling saints and truly most of them are smiling. Never ever have I seen smiling faces in churches before. Such an uplifting experience.

Sadly this beautiful and mesmerizing part of the country is neglected by my fellow countrymen. The county is far from the capital and western Hungary (well partly because of bad infrastructure) and is a poor region. There is ?rség next to Austria which is more popular and full of tourists and in a better position in the richer part of Hungary close to the west. Nice place but bit overrated. My heart remains in Szatmár.

Hi Timi: I was also surprised that more tourists had not discovered this lovely area of Hungary. But I think the locals are working to change that. I just hope it doesn’t ruin it when people begin flocking in. I’m so glad you liked my article, and thanks so much for your comment.

I recently learned this is where my 3rd great Grandmother (Tessie Simon, im sure it is pronounced/spelt differently before they came to America ) was from & I am so Amazed at the beauty & history of this small but interesting place. I would love one day to visit & see all the wonderful things it has to offer but for now I thank you for putting the pictures with the story so now I have some kind of visual knowledge of how my ancestors lived.

How interesting Braandi! I hope you get to visit that part of the world, as I found it fascination and just a little mysterious.

The most intriguing cemetery! I love that you offered a glimpse of a destination that still remains quite forgotten/undiscovered by the world. It would be very interesting to dig deeper and learn more about the local legends..I´ve always been under impression that Eastern Europe has SO much to offer and your post certainly didn´t disappoint in that regard!

Hi Jay: I was told that there is no other cemetery in the world like it and I believe it. This part of the world was such an amazement to me and I can’t understand why it doesn’t have more tourism. I’ll undoubtedly go back at some point to learn more.

Beautiful photos!

Most interesting article!

Thanks More Than Red. It’s definitely an intriguing part of the world.

The wooden church looks a bit like the Stave churches in Norway but with superb frescoes inside. I’ve really enjoyed your tour of Szatmar, a very untravelled part of Hungary.

Thanks Mark, this area of the world was a surprise to me, and one that I very much enjoyed. There’s definitely more to Hungary than Budapest and Lake Balaton, though those two places deserve their great reputations as well.