The fuzzy silhouette within the long rod of amber seemed familiar, yet I wasn’t quite sure what I was seeing. I turned my head sideways and squinted to better focus. With a start, I realized I was looking at the complete body of a lizard that had been trapped in amber. The specimen at the Amber Gallery and Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania, is rare. Of the millions of pieces of amber that contain inclusions, only six lizards have ever been discovered.

In part, it was these mysterious inclusions that had drawn me to the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia. I wanted to know more about the semi-precious material known as amber, and to learn how it became one of the most prized materials of the ancient world. Perhaps most of all, I wanted to understand how plants and insects came to be trapped inside.

Amber may have been the world’s first precious material. Thousands of years before the Silk Road or the Salt Road existed, amber was being collected, processed, and traded throughout the Asian, European, and African continents. Archeologists have discovered amber pendants from the late Paleolithic Age (circa 12,000 B.C.) and amber jewelry workshops that date to around 10,200 B.C. Baltic amber beads reached the central Mediterranean by 1600 B.C. A vessel carved in the shape of a lion, along with 90 amber beads, all dating to the 13th century B.C., were found in the Royal Tomb at Qatna in Syria. Modern testing indicates the raw amber used to make them was likely imported from the Baltic region.

By the 1st century AD, the Roman Empire was carving the semi-precious material into elaborate decorative items, small implements, and eating utensils. To meet the huge demand for raw amber, a trade route developed. It began on the shores of the Baltic Sea, traversed present-day Poland, and continued south through Eastern Europe to the Adriatic coast of present-day Italy. From there, it went overland across the Italian peninsula to Rome. This Amber Way, as it became known, was the precursor for all trade routes connecting north and south Europe.

The amber trade came to a screeching halt upon the fall of the western Roman Empire in 475, but reemerged in the 10th and 11th centuries when new trade agreements were established with Egypt, Arabia, and the Far East. By the 12th century, the Crusaders had converted much of Europe to Christianity and, in the process, revitalized the Amber Way. Suddenly, everyone wanted Rosary beads made of amber. Many of the returning Crusaders settled along the Baltic coast. They seized all amber-producing lands and for the next 300 years exercised a monopoly over collecting, mining, working, trading, and transport of the gem along the Amber Way. By the middle of the 15th century, Polish and German guilds had largely taken over the amber trade. They were followed by the Prussian government, which purchased the rights to the amber fields in 1642. The Kingdom of Prussia ceased to exist after World War Two and the tiny pocket of land tucked between Poland and Lithuania reverted to Russia. Today this Kaliningrad province of Russia produces 90% of the world’s amber.

Despite being crucial to the economy of early Europe, amber was poorly understood. Greek myths variously claimed that it was crystallized bird’s tears, Lynx urine, or concentrated sun rays washed ashore by the sea. Others insisted it was petrified fish roe or hardened sea foam. One of the most intriguing legends is that there were once two suns in the sky, but the gods banished one into the ocean, where it instantly solidified. It hit the bottom of the ocean and splintered into thousands of fragments which continue to wash ashore to this day in the form of amber.

Even scientists couldn’t agree. They theorized it was a substance secreted by whales, formed from honey, produced by giant ants, or (perhaps the closest guess) that it was tree sap. Today we know that amber is fossilized tree resin from ancient pine trees. Fifty-five million years ago, these pine forests covered the plains that existed prior to the formation of the Baltic Sea. When damaged, they extruded a thick, sticky resin to repair the wound. It oozed down the trunk, trapping insects and vegetation in its path. The resin hardened and dropped to the ground, where it was subsequently carried to the sea by rains and flooding. Though the pine forests have long since become extinct, the amber that they produced continues to be washed up with every major storm, and modern technology has developed safe methods for mining the soft soils within which the gem is embedded.

There is less agreement on the properties of amber. Though its most popular use is decorative, it has always been used in folk medicine. In ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder claimed it cured ailments of the neck and head. The famous Roman physician, Calistratus, wrote that amber protects from madness and that powder of amber mixed with honey cures throat, ear, eye, and stomach ailments. In China, a mixture of amber and opium was used as a tranquilizer and to control spasms. Japanese Emperors believed that red amber would purify the blood. Amber teething rings were given to infants and amulets were believed to offer protection from evil. The gem was ground into a powder and made into a salve to treat skin conditions. Today, amber is a popular incense and it is increasingly being used in cosmetic treatments to improve skin elasticity and remove fine wrinkles. Amber oil, which has known antiseptic properties, is used to heal wounds and strengthen immunity.

Though I had intended to buy an amber ring in one of the Baltic countries, jewelry stores specializing in amber began to appear in Poland. I held off as long as I could, but exquisite pieces in their display windows eventually lured me inside. Once I began seriously looking there was no turning back. In Krakow, I chose a lovely transparent caramel-color ring mounted in silver, as well as two small lumps of raw, unpolished amber. The certificate of authenticity provided by the shop gave me little confidence; anyone can print up a piece of paper. But I assumed that a shop with such magnificent pieces on display must be reputable.

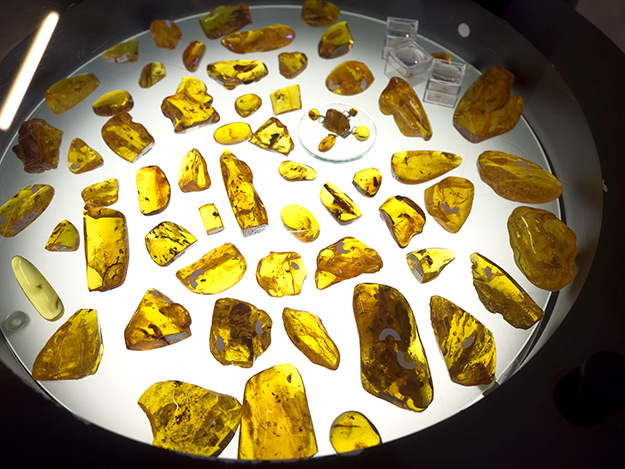

My certainty was tested when I visited the Amber Gallery and Museum in Vilnius, Lithuania. In the lower level museum, glass cases displayed specimens in some of the 215 known colors of amber and a light table showcased transparent pieces containing an astonishing array of inclusions. I learned that only about 10% of all amber is the transparent, golden to caramel color variety. Opaque yellow, the most common color, occurred when high temperatures caused the volatile components of resin to evaporate and form thousands of small gas bubbles that refract light. Red amber was formed when the resin stayed in the air for a long time and was subject to intense sunlight or fire. Natural oxidation took place and the amber interacted with oxygen, becoming darker. Black amber resulted when the resin was thoroughly contaminated with bark, soil, and vegetation. This high level of impurities makes black amber extremely fragile and more difficult to work, thus finished pieces are highly prized. Both white and green varieties are rare, but the rarest is blue. With only two in every 1,000 pieces exhibiting a blue tint, this variety is considered nearly extinct.

As with most items of high value, counterfeiting has become widespread. Scientists discovered ways to make synthetic amber as far back as the 19th century. These days, customers are often duped into paying high prices for fake amber. Fortunately, even the most uninformed buyer can apply some simple tests to ensure the authenticity of the pieces they are considering. First, smell it. The amber should have a distinct pine tree resin smell. Synthetics will smell sweet or like burning plastic. Second, rub it between your hands until it gets warm. Once again, it should exude the fragrance of pine resin. Most reliable is the “float” test. True amber will float in a 10% salt water solution, while fake amber will sink to the bottom. Any reputable amber shop should have a glass goblet filled with salt water available for such a test.

The jeweler from whom I purchased my ring told me that the presence of twigs, grit, and other vegetative material inside the cabochon guaranteed its authenticity. That information was completely false. Workshops in Russia are producing plastics that look like real amber, right down to the inclusions. Copal, a much younger type of tree resin, is often represented as amber. Though inclusions such as insects can be inserted in copal, they often appear too big and too perfect. The best way to determine if a piece is copal rather than amber is to place a drop of acetone (nail polish remover) on it. Copal will become sticky, while amber will not be affected.

So, is my amber or a fake? I’ll probably never know for sure, but when I buff the two small chunks of amber, they exude no scent of pine resin. They seem too perfect, too glassy. My guess is that they are glass, and that I got duped! As for my ring, when I rub the cabochon vigorously it does smell of pine resin, so I’m calling it real. At least that’s my story and, as they say, I’m sticking to it.

“the Teutonic Knights had converted much of Europe to Christianity“ The Teutonic order wasn’t even formed until the middle of the 12th century. It was a little bit late to convert anyone to Christianity by that date; Poland converted in the middle of the 10th century, for example.

Hi John: Well, I AM embarrassed! I always try to research things thoroughly before writing, but this time I messed up. I’ve just spent the last two hours consulting my notes on that article and delving back into the research I did. The only thing I can figure is that I confused the Teutonic Order with the Crusaders, who were their precursors. I’ve made the appropriate changes and believe it’s correct now. If not, let me know. I’m always open to information that can make my writing more correct.

It is not illegal . Amerikas mentality makes “everything illegal “.

It is natural to pick (look) for an amber at the shore .. Same as natural to smell the flowers bouquet .

Not in Russia, at least not in Kaliningrad, Daiva. There, it’s illegal.

I grew up at the Baltic Sea and when on the beach we used to look for washed-up amber. We often found small pieces and mother had an amber neclace. Most pieces we found were of the clear type. Pieces with small inclusions could be found once in a while.

Hi Peter: I was told that it’s illegal to collect or even pick up a piece of amber in the Russian art of the Baltics (Kaliningrad and environs), but the read an article that showed photos of locals dredging along the beaches illegally. Wonder if you know anything about that?

I wanted to point out that Prussia ceased to exist after World War II, not World War I as stated in the article.

Hi Diane: You are absolutely correct. Thanks for the heads up. I’ve made the appropriate change to the article.