Ockham’s Razor is a scientific principle that is often paraphrased as “All other things being equal, the simplest solution is the best.” Today this principle is often taken as a rule of thumb that advises economy or simplicity, especially in scientific theories. This summer, masons and mechanics, farmers and welders, scientists and a pastor dedicated themselves to the theory of Ockham’s Razor as they brainstormed methods to create low-tech solutions to big problems that persist across the globe.

Converging at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for the three-week long International Development Design Summit, these 61 inventors from 20 countries divided into ten teams that worked round-the-clock to develop and build prototypes of low-tech devices for developing nations, designed to make life a little easier for the poor peoples of the world. Prototypes ranged from an inexpensive incubator for low-birth-weight babies to a rope system that could help craftswomen in the Himalayas get their products to market, but in my opinion, the two most interesting inventions to emerge from this year’s summit are a low-cost charcoal crusher and a scheme to produce electrical power with incidental effort as people go about their everyday tasks.

I was personally made aware of the need for a charcoal crusher when I visited Tanzania last year. My safari driver stopped one day to buy charcoal for his family’s cooking needs. The whole affair seemed cloaked in secrecy; the bags were nowhere to be seen upon arriving at the store and my diver disappeared into a back room to negotiate for the purchase. Finally, a tall young man emerged from around the rear of the store, toting an enormous sack, which was strapped to the roof of the jeep.

Afterward my driver explained that, for decades, the populace has been cutting down trees to make charcoal for cooking. Of late, the government of Tanzania has ramped up efforts to keep people from cooking with charcoal, encouraging the use of LP gas instead. However, gas is an expensive commodity in a country where people live on just a few dollars a day, and no one heeded the government’s suggestion. Perhaps realizing the futility of this effort, the government is now attempting to solve this problem in another manner; they are instead encouraging the production of charcoal from burnt corn cobs and crushed sugar cane. Unfortunately, this does not address the health risks associated with eating foods that have been cooked over charcoal, which is not clean-burning and generates indoor pollution that has been linked to deaths on the same scale as malaria and tuberculosis globally.

One way to make charcoal produce fewer emissions is to pulverize the charred agricultural waste into denser briquettes. A $2 metal press is already available for crushing powder into charcoal briquettes, but there is no device available to crush the burnt cobs into powder. Currently, Tanzanians stomp on bags of burned cobs or beat the sacks with heavy sticks. When the bags are emptied, the crusher is momentarily engulfed in a black cloud, inhaling the dust. After a few stomping sessions, the bags must be replaced, a recurring expense.

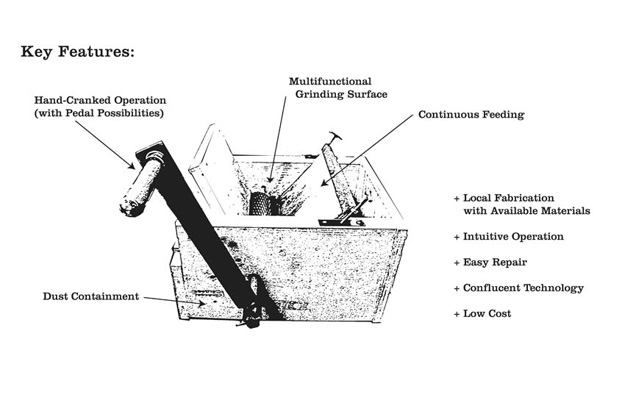

To solve this problem, one of the IDDS teams decided to develop a low-cost, low-tech device to crush the corn cobs. Their prototype looks like an oversize mouse trap with a hand crank. The user spins the crank and feeds the blackened cobs through a hopper. The grinder drops the powder into a container where it’s mixed with other ingredients into a cookie-dough consistency for briquettes. The simple contraption can crush six pounds of cobs in 10 minutes.

Another team decided to address the fact that 1.6 billion people around the world have no access to electricity and must either use fuel lamps or stay in darkness every night. With lives that are already incredibly difficult, few of these people would be willing to labor to generate electricity. “But if the effort is incidental as they go about some regular task, people don’t seem to mind putting in that extra 10 percent,” says Jay Pagnis, a mechanical engineering student from India. His team focused on treadle pumps – foot-operated devices used to irrigate farmland in Asia and Africa. Many country farmers step on and off these StairMaster-like contraptions to pump water for an average of four hours a day.

The team designed a generator attachment that fits in a wooden frame and hooks the pump’s treadle to a turning wheel, which charges a couple of store-bought batteries. After the day’s work, a farmer can unhook the rechargeable batteries and use the power to light a 5-watt compact fluorescent lamp – the equivalent of a regular 25 watt incandescent lamp – for four hours. The mechanism can pay for itself in six months and if it breaks down it is simple enough to be repaired by a local bike mechanic.

Having traveled to remote pats of India, I am well aware of the abject poverty in this country. Despite the fact that I was staying in the home of a fairly well-to-do village elder, water was scarce and what little was to be had was hauled in each day by tanker and pumped to a rooftop tank. The few hours of electric service that was available each day during was used mostly to pump the water to the roof. This affordable, low-tech generator attachment will undoubtedly be a welcome innovation to millions of people around the world who are not as fortunate as those of us who can just turn on a spigot or flip a switch.

As the Franciscan friar, William of Ockham, said back in the 14th century, the simplest solution is definitely the best.

Incandescent light bulbs will soon be phased out because they waste a lot of energy.,”;