The urgent need to pee woke me at 5:30 a.m. I swung my legs over the side of my bamboo cot and gingerly tested my right ankle, which I’d twisted the previous day on a loose rock. It was much better, but I wasn’t taking any chances in the rock-strewn landscape. Carefully, I picked my way to a spot away from any cots, lowered my pants, and squatted, praying that I was far enough away that no one could see my white moon butt or hear my explosive pent-up gas. There are no toilets at the Danakil Depression.

The camp sprung to life as the rising sun scrubbed away the last wisps of pre-dawn dinginess. Our cook emerged from his hut and began to rattle pots and pans. People stretched and yawned, fighting the urge to go back to sleep. A worker began digging a trench, taking advantage of the relative coolness of the early morning hours (temps had fallen to a tolerable 97 degrees overnight). In the fresh light of day, I looked down at my clothes and realized that I was filthy. Between falling down the day before and sleeping in the open air, my pants and t-shirt were covered with dirt.

Fortunately, I’d brought along a second set of clothes, but the challenge was finding a place to change. The only place that afforded any privacy was our jeep, so I climbed inside, slunk down in the front seat, and peeled my t-shirt over my head. I looked up to grab my clean shirt and, too late, realized my mistake. I was not the first woman in this camp to seek privacy in a vehicle and the local boys were savvy. Six sets of eyes peered through the windows as I sat there in my bra. I laughed and just got on with it, but changing trousers was out of the question; it’s the price I had to pay for not wearing any underwear.

My rustic campsite was in Ethiopia’s Danakil Depression, the hottest place on earth and home to some of the world’s most surreal volcanic landscape. It had taken most of the previous day to get here. Our caravan of jeeps bounced for hours on washboard roads that snaked through barren gray-brown mountains. When the road finally dipped, we pulled over and walked to a precipice for our first view of the Danakil Depression.

Located at the northern end of Africa’s Great Rift Valley, this entire area was once under water. Initially, it was uplifted by the colliding of tectonic plates, but when the Arabian Plate and the two parts of the African Plate (Nubian and Somali) began pulling away from one another, the place we today know as Danakil began to sink. Picture two people pulling a string of taffy from either end. As the two ends of taffy move further apart, the middle sags; the Danakil Depression is the middle of the taffy. Over the eons, the landmass sank lower and lower, until it was more than 400 feet below sea level.

As we descended into the depression, the temperature began to ratchet up. By the time we reached our campsite in the town of Hamedela, we were nearly 300 feet below sea level and the mercury had soared to 115 degrees. It is difficult to believe that people actually live in these brutal conditions, in rudimentary huts built of acacia branches. They have no electricity and no toilets. They cook over open fires and have to haul in every stick of wood they use. They drink mostly milk and blood from the goats and sheep they herd, though water is hauled in by the truckload. Riding along in my jeep the day before, with the wind blasting my face, the temperatures had been tolerable. But each time we stopped, the oppressive heat smothered me like a thick blanket. I couldn’t even imagine building a fire or cooking a meal without withering.

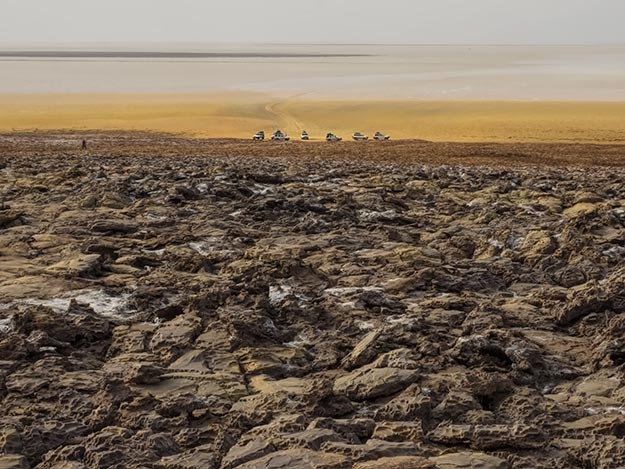

After a decent breakfast of scrambled eggs and pancakes, our caravan headed deeper into the Danakil wilderness. The bumpy gravel road quickly gave way to endless snow-white salt flats, relieved only by polygonal crazing and small brown humps on the horizon that became camels as we got closer. Dozens plodded past, roped together in a single file, laden with heavy bags of salt mined from the flats.

After three or four caravans had passed, we drove to where the Asale Red Rocks jutted abruptly from the white salt sheet. Near the foot of the rocks, an incongruous water hole had opened up. I was tempted to jump in for a refreshing swim but hesitated. With the extreme temperatures and no fresh water around for miles, I had an inkling about what would happen when the swimmers emerged from the pool. Sure enough, the water dried in seconds, leaving their bodies covered in crusty white salt.

On the move again, we headed for a thin brown line that was barely visible on the misty horizon. As we drew nearer, gray-brown towers of crystallized salt, sculpted into bizarre jagged formations, came into focus. We mounted a small rise and I gasped. The snow-white salt flats butted into a brassy yellow landscape, as if someone had drawn a line and said, “Here begins the sulfur deposits of Dallol.”

The name Dallol, which translates to “colorful” in the Afar language of the region, couldn’t be more apt. At nearly 400 feet below sea level, volcanic activity occurs close to the surface. Burbling pots of acidic sulfur, potash, and copper rise up in a riot of black, yellow, gold, gray, white, green, and even blue hues. A twenty-minute climb brought me to the top of the hydro-geothermal deposits, where mini geysers spewed boiling hot, mineral-laden water. I stepped gingerly, choosing built-up places well away from steam vents or pools of beautiful but deadly acid.

Back on the flats, we drove along the base of the hill to see the giant crystallized salt cliffs that had earlier marked the horizon. The ground didn’t feel steady underfoot and sure enough, I crashed through at one point, into a liquid brown ooze that coated my left shoe like Peptol Bismol running down the inside of the bottle.

A bit further on we stopped again at Lake Assal, an oval pit of yellowish-brown liquid that burbled and spit. Though it looked like a boiling lake, this water was actually cold. My driver explained that it was an oily liquid that contains copper, potash, and aluminum, among other metals. He dipped his silver crucifix and chain in the solution and wiped it with a rag; it came out gleaming. The lake water is safe to use topically, and the mud from the edges of the lake is said to be good for skin conditions. Drink it though, and you die.

Our last stop was the place where Haro people work day after day under a relentless sun, breaking and chipping salt into perfect rectangular slabs. The Haro are Muslim, thus they work every day except Friday. The Afar people, who are Christian, load the completed slabs onto their camels and tether the animals together in long caravans. They set out on foot across the salt flats, leading their camels nose-to-tail in single file. Their destination is the village of Berhare, a three day trek away.

The camels have the worst of it though, being forced to carry incomprehensibly heavy loads of salt strapped to their back and sides. In earlier times, the journey took seven days. Even though it is shorter these days, the backs of the camels are badly scarred from the weight and, probably, from salt grinding into their hides. Some owners put thick pads on their camels’ backs, but others have only a single thin pad. As one of my guides said, “There are no animal rights in Ethiopia. They’ve been doing it this way for a thousand years and it will likely continue for another thousand.”

By mid-afternoon we were on our way back to the airport in Mekelle, with a stop in Berhale for lunch. After a mediocre meal, my bladder started to scream again. I made my way across the dirt-floored restaurant and through a canvas flap leading to the rear. Past an outdoor kitchen shaded by blue tarps, beyond three goats munching on discarded bones (and, incomprehensibly, a broom handle), I found the squat toilet, a makeshift contraption consisting of bamboo poles wrapped in salvaged UNHCR (United Nations High Commission On Refugees) tarpaulins. I closed the “door” (a swath of tattered fabric hanging from a rusty rod), but the wind promptly flapped it open, exposing me to anyone walking by.

That was the least of my worries. By that time I’d been holding off on “pooping” for a day and a half. I placed my feet on the concrete humps on either side of the ceramic pan and squatted, gingerly placing my fingertips on the ground in front of me to balance and take pressure off my bad left hip. I clutched, aimed for the hole, and willed myself to pee only. Pee I could air dry. But pooping would require wiping. Already teetering precariously, there was no way I could release one hand to wipe. Midway through the deed I lost my balance. Pee squirted over the concrete humps and onto my shoes as I toppled forward, both hands landing squarely in a puddle of urine as I struggled to right myself. At least I’d managed to hold off “number two.”

By the time I hopped into the 4WD for the final leg of the journey back to Mekelle, my intestines were rumbling. I tried to focus on the landscape but my sole thought during the two-hour drive was getting to a real toilet. Back at the offices of Ethio Travel and Tours (ETT), a staff member directed me to the hotel next door. I followed the signs to a disgustingly dirty toilet with an inch of water on the floor. No way I could even put my backpack down. With no other toilet available, and even though it was more than five hours before my flight, I had ETT take me to the airport, where I at least had use of clean, modern toilets with running water and dry floors.

Visiting the Danakil Depression isn’t the easiest or most comfortable tour I’ve ever taken. But it was worth every second of discomfort to see this otherworldly landscape that exists nowhere else on earth. My only regret is that, with my bad hip, I couldn’t do the four-hour trek at night to the rim of the Erta Ale Volcano, which has one of the largest open pits of exposed magma in the world. Maybe someday. I ever get brave enough to have a hip replacement, you can bet I’m going back.

Denkil not in Ethiopia in Eritera why pepole took eriterian history give to Ethiopia

Hi Barbara,

I am going to Ethiopia in December with my boyfriend and we are looking to find a guide to go to the Danakil Depression. Where you happy with the price and service of the agency you used?

Thanks

Hi Rosaria: I wouldn’t give them the best recommendation. There was confusion about the scheduling, poor communications, and I came up missing $300 from my backpack at the end of the trip.

Your Danakil Depression experience is definitely one for the books; the test of discomfort and the surreal (and brutal) landscape. I am totally in awe of your adventures and your writing prowess, Barbara. Thanks for sharing!

Thank you Giovanni! I appreciate you taking the time to comment, and for your kind words.

The more I read about this place, the more I want to go there. This is the first I’ve read of the ‘practicalities’ of being female and travelling there though. Has it put me off? Not in the slightest.

Good for you Anne! Believe me, it’s worth all the inconveniences. Ethiopia is truly astounding.

WOW! What an incredibly interesting place! One for the bucket list

Hi Rebecca: I agree! Ethiopia should be on everyone’s bucket list.