Salt. It’s on every restaurant table and in most every home. We reach for the shaker without regard for its provenance – where it comes from, how it’s processed, or the means by which it arrives on grocery store shelves. In the 21st century salt is an abundant, inexpensive commodity that we take for granted. Yet it wasn’t always so.

Though there is no written documentation to prove the use of salt in prehistoric times, it is commonly accepted that salt must have been an indispensable ingredient in eastern Europe as far back as 6,600 B.C.. As hunter-gatherer cultures began shifting to more complex economic systems based on farming and animal husbandry, salt would have been required to maintain the health of livestock, process milk, tan leather, preserve and season food. Salt was unevenly distributed across the region and by the Middle to Late Bronze Ages (16th to the 13th centuries B.C.), salt-rich communities were exporting to salt-poor regions in far southeastern Transylvania, west to the Hungarian Plain, and likely as far as the Balkan peninsula.

The first written records of salt production and trade in eastern Europe appeared during the Medieval Ages. A document issued by the Hungarian chancellery in 1075 mentions a salt custom house “in the citadel called Turda” and in a subsequent document dated 1271 “the salt mine in Turda” was offered to the Head of the Catholic Church of Transylavania. In the spring of 1552, a report made by royal inspectors called the salt mine of Turda the most important in Transylvania. Indeed, the salt deposits in this part of the Transilvanian plateau cover an area of about 17 square miles and average 820 feet in depth, with some deposits being nearly 4,000 feet thick!

To my delight, I learned that the Salina Turda Salt Mine, which closed down in 1932, had been reopened as a tourist attraction in 1992. On my last day in Cluj-Napoca I hopped on a mini-bus for the 35-minute ride to Turda, where I caught one of the shuttle buses that run continuously between the town center and the mine. After a short briefing by an employee who showed me a large map and suggested the best route to take, I began a long climb down through a tunnel that might have been bored by a giant mole. As the temperature plummeted, the walls began to sweat, transforming them into black mirrors. Fascinated, I reached out to touch the slick surface and recoiled, repulsed by the clammy, oily feel of the weeping black salt.

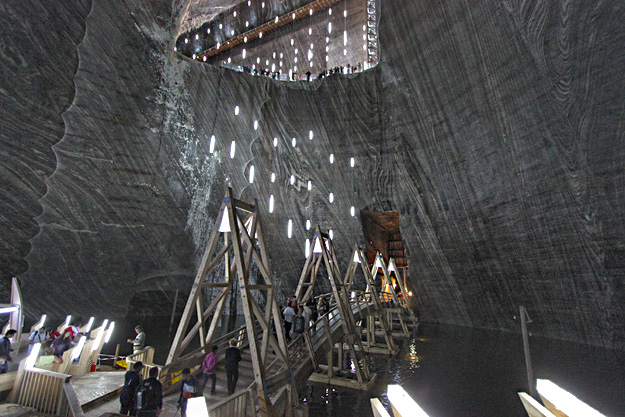

At the bottom of the stairs the tunnel widened into the Franz Josef Gallery, a horizontal passage that was completed in 1870 to facilitate the movement of salt to the surface. Being careful not to slip on the polished salt floor, I followed passageways that branched off to echo chambers and rooms displaying ancient extraction and transport machines, eventually arriving at the Rudolf Mine, the last area that was actively excavated at Turda. A wooden walkway, cut into a ledge at the top of the cavern, provided a bird’s eye view of the 138-foot deep rectangular excavation.

Rather than suffer long lines waiting for the only elevator, I opted for the 172 steps that led down to the floor of the mine, where families were enjoying an amusement park complete with mini-bowling, mini-golf, merry-go-round, children’s playground, billiard tables, and Ferris wheel. Off to one side I found a second observation platform overlooking the bell-shaped Terezia Mine, which plunges an additional 393 feet and features an underground lake with rowboats.

Though most visitors were there for the entertainment, I was fascinated by the geology of the mine. Salt stalactites hanging from the ceiling grow to nearly ten feet in length before breaking off from their weight. The sheer walls are zebra-striped in shades of black, grey, and amber, evidence that layers of evaporated salt were laid down over eons as inland seas alternately flooded and receded from eastern Europe. Plate tectonics folded and tilted the salt layers, creating a fascinating pattern of stripes and wavy lines that was exposed when the mines were excavated. These geologic forces occurred deep underground, thus the salt at Salina Turda is exceptionally pure, testing at more than 99% sodium chloride. Because of its purity, researchers theorize that in addition to being used by the local community and mined on an industrial scale for export and trade, salt from the Turda mine was also an exotic good with a highly symbolic value. Having the resources to own a product that was as valuable as gold implied power, vitality, connection with sacred places, and even immortality.

Salt has long been used in religious ceremonies. Until recent times, a small amount of salt was placed on the lips of a baby being baptized in the Catholic Church. In Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting, The Last Supper, Judas Iscariot has spilled the salt, which is considered to symbolize bad luck and/or evil. From this comes the practice of throwing a bit of the white stuff over our left shoulder whenever salt is spilled, an action believed to ward off the devil. The bible is rife with symbolic references to salt: Lot’s wife was turned to a pillar of salt when she looked back at Sodom and Gomorrah and Jesus called his disciples salt of the earth. Buddhists believe that salt repels evil spirits and Jews still dip their bread in salt on the Sabbath when passing the bread around the table after the Kiddush. Salt was widely used to cast spells in the eastern European folklore tradition and is still considered a magical substance in the Wicca religion.

As Margaret Visser has said in her book, Much Depends On Dinner:

“Salt is the only rock directly consumed by man. It corrodes but preserves, desiccates but is wrested from the water. It has fascinated man for thousands of years not only as a substance he prized and was willing to labour to obtain, but also as a generator of poetic and of mythic meaning. The contradictions it embodies only intensify its power and its links with experience of the sacred.”

Given salt’s long history with the sacred, converting the Turda mines to an amusement park struck me as slightly profane. I shared my thoughts with another visitor as I was waiting in line to exit and learned that the mine also serves as a medical treatment facility. The constant air temperature, virtual lack of allergens, presence of aerosol salt particles, and predominance of positive ions in the air have been found to have a curative effect for patients with severe respiratory conditions, many of whom are children. The amusement park was installed to entertain kids who must spend long hours breathing the air at the bottom of the mine. As I climbed to the surface I breathed deeply, filling my lungs with positively ionized air, on the off-chance that the ancients who believed in the magical properties of salt knew something we don’t.

How to visit the Salina-Turda Salt Mine in Turda, Romania:

Turda can be reached from Cluj-Napoca by mini-vans that leave hourly from the corner of Piata Mihai Viteazu and Strada Ion Popescu Voitesti. The cost is 35 Lei (about $10 USD) and the trip takes approximately 35 minutes. The shuttle bus from Turda to the mine is approximately $2 USD each way. The mine is open seven days a week, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., with the last entry allowed at 4 p.m. Admission is approximately $6 USD per person for adults, $3 USD per person for children and students, and about $3.60 USD for retirees.

Check prices for accommodations in Cluj-Napoca at Booking.com, Hotels.com, or HotelsCombined.com. Read reviews about hotels and guest houses in Cluj-Napoca, Romania at TripAdvisor.

Disclosure: This article contains affiliate links to hotel booking sites. If you click on any of the links and make a booking, I may earn a small commission, which keeps this blog free to read.

Hey barbara!

Thanks for sharing this great information. Let me tell you that I didnt have a clue about this wonderful site and had to see it on my own. went to Rumania for business trip and had a great time there! Spent the whole day and wasnt enough! great article, congratulations!

Thank you so much Omar. I’m happy you found it so helpful!

I am very glad that I found your blog. I did not know anything about the salt mines in Romania. Incredibly interesting photos. I really want to visit this place! Thanks for sharing!

You’re welcome Tori. Glad you found it interesting.

Looks great. I’m from Targu Mures, a town close to the salt mine, and it’s a must, if you are in the area.

I will add it to my must see someday list, Calin. Thanks for the suggestion.

I visited it very recently, I would like there to be a place nearby to have a snack because if you stay here to walk the food options are very scarce.

Barbara, I think you should also visit some places like Yucatan, I recently ventured to travel to Mexico and I love that the stalactites of this city are quite huge, these really when I saw them became minuscule.

I know this post has a lot of time too but you can see my comment, if you visit Mexico I hope you upload some experiences and comments later, I would love to read abou it 🙂

Hi Allison. I’ve traveled extensively in Mexico. You can see all the articles I’ve written here: https://holeinthedonut.com/category/mexico-travel. They’re six to a page in chronoligicalorder with the most recent shown first. Just keep clicking the arrows at the bottom for older articles.

Romania is one of the most beautiful countries in Europe. You must visit Transylvania and write more. You can tour with other people who are just as passionate as you.