The young man was so intent upon spray painting the brick wall that he didn’t notice me. He was tall and willowy, wearing baggy jeans and checked shirt, but with a respirator covering his nose and mouth it was hard to tell much more. His mural, on the other hand, screaming out in blood-red block letters, was anything but nondescript. I interrupted to ask why he was painting a mural on a brick wall when he knew it would likely be covered over within days.

He paused and swiped at beads of sweat running down into his eyes. “Just for the love of it. It’s the way I express myself,” he replied. He didn’t much care that other street artists would paint over it. “There’s sort of an unwritten agreement that we don’t paint over other work when it’s brand new, so at least I know it will be seen for a little while. And when it’s gone I’ll paint another one.”

Travel blogger Heather Cowper and I had embarked upon a walking tour earlier that day, specifically to view the street art in Bristol, England. We’d begun on Nelson Street, home to See No Evil, the UK’s largest permanent street art project. Inspired by large-scale street installations in Melbourne, Australia and Lisbon, Portugal, street artist Tom Bingle, better known by his street name Inkie, began looking around for a location in Bristol that would be appropriate for such an installation. With blocks of brutally depressing 1960’s era buildings, many of which had fallen into disrepair, the Nelson Street neighborhood was the perfect candidate. Bingle, along with local music producers and gallery owners, appealed to the Bristol City Council, making a case that not only would street art in Bristol be a catalyst to drive redevelopment of the neighborhood, it would also attract tourism. Though some Conservative councillors insisted it was a waste of money, the more liberal won out. The Council donated £40,000, on the condition that it be matched by private donations. With government approval under their belts, the organizers spent another year planning and winning support from residents, businesses and building owners.

The first See No Evil, held in August of 2011, drew acclaimed street artists from around the world, each of whom used a building, wall, fence, or in one case, an overpass as their canvas. The event, which culminates with a “New York style block party” and a three-day music event, was repeated in 2012. Thirty selected artists were invited to paint over the existing canvases, though the public voted to preserve three of the pieces from the previous year.

See No Evil, though an inspired project, was far from the first instance of street art in Bristol. Heather and I were standing in the Stokes Croft area of the city as I chatted with the young man who had been so intently focused on his piece of wall. Plagued with derelict housing, the neighborhood has long been a magnet for such displays. All around us, in every direction, walls, fences, and even entire buildings were covered in paintings that conveyed messages of political and social discontent.

These days, artists are not just tolerated in Stokes Croft, they are encouraged. In one case, they are allowed to live in tents and RV’s in a weed-choked parking lot aside the crumbling abandoned Westmoreland House and the Carriage Works building, in return for ensuring no one goes inside. But it was not always so; tolerance for their particular art form was a gradual process, and it may not have happened but for the influence of one Bristol-born artist, known only by the pseudonym Banksy.

Banksy’s paintings began mysteriously appearing around Bristol during the late 1980’s. Best known for his stenciling style, he claims to have seized upon the idea when he noticed the stenciled number inside a trash bin, where he was hiding from police. He realized that using stencils would allow him to complete his work much faster, thus eluding the cops. Except within his circle of peers, Banksy operated in relate obscurity in the early years, especially since his true identity has always been unknown. His fame began to grow when he came to the attention of high profile people such as Christina Aguilera, who purchased two of his prints for £25,000 in 2006. Today his works sell for up to £500,000 and in some cases they have been auctioned off in-situ, leaving buyers to deal with removal of wall or other surface upon which it was painted.

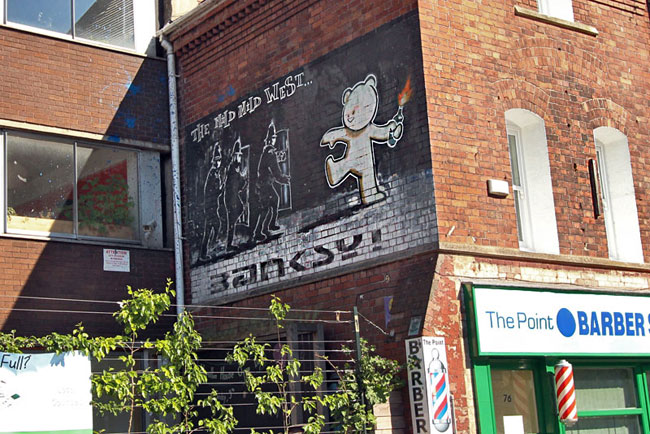

As a result, street art has entered the mainstream art world, no longer relegated to the status of graffiti. Journalist Max Foster, writing in December 2006 about the growing interest in street art, called this “the Banksy effect.” A few of Banksy’s pieces can still be seen around Bristol. In Stokes Croft, his famous painting of a teddy bear throwing a Molotov cocktail at riot police is preserved on a high brick wall. Another, showing a naked man hanging from a windowsill while his lover’s husband peers out the window in search of a suspected Lothario, is still visible despite being splashed with blue paint by vandals. A third is harder to spot. Painted at the waterline on The Thekla, a rusty old scow that has been converted into an after-hours club, the image of Death rows a small boat, perhaps across the River Styx.

Banksy has become so popular that wannabees have emerged. Heather showed me a photo on her cell phone of a little girl drifting up into the sky while clutching a red balloon, a classic Banksy motif. We stopped into a street art store in Stokes Croft to ask the opinion of the experts, who decided that the new piece had been done by a copycat who hadn’t quite gotten Banksy’s style down pat.

I’ve long struggled with how I feel about street art. The act of “tagging” – panting one’s initials on the side of buildings – still disturbs me. I find it impossible to accept this as art; it’s just graffiti to me and probably always will be. But over time, I’ve come to see most street paintings, regardless of style, to be inspired and thought-provoking, and that was certainly the case with the street art in Bristol.

Many thanks to Heather Cowper, my Bristol-based travel blogging friend, who not only took me around her home town, but let me crash at her house for two weeks. Read more about Bristol’s street art scene in this story by Heather, or check out her Flicker gallery of Bristol street at images.

its a joke

Excellent post and lovely art. I love that tunnel!

Thanks Christopher. Yes, the tunnel, and all the other art for that matter, was fascinating.

It’s encouraging to see that when street art is sanctioned and encouraged that it can benefit both artists and the surrounding community. Very interesting story.

Thanks Mary. I was just amazed by the amount of creative talent in these street artists.

I love Banksy’s style, but never knew he was from Bristol. He kind of reminds me of Keith Haring for tagging up public spaces soon leading to international fame. These guys drew/painted from a simple modern palette, something that everyone could react to and understand. Nothing too abstract. Simple design and simple colors. I love it.

Agree Tiana – and in Banksy’s case, his art is often infused with a political message, which makes it even more interesting to me.

Bristol is really a great place to come if you enjoy street art – I walk down Stkes Croft every day and there’s always a new piece appearing. The latest Street art festival in Bristol is UpFest which we did’t manage to get to when you were here and is Bristol’s south of the river district doing something similar to See no Evil.

Wonderful. I love to see cities encourage street art which I suspect cuts down on graffiti and encourages people to take more time in creating more colourful, meaningful and artistic pieces.

There are some really beautiful examples there. I’m glad to see that the government was able to come together and make the decision to support public art. Public art and expression are great ways to bring back interest in a derelict part of town, and this sure seems to be working!

Hi Shawna: It IS working. The festival has become one of the largest tourism draws in Bristol.

Whether or not they use street locations as a canvas, I think there is a great deal of unrecognized talent there. I wonder if & hope that they earn a living in art or if they are forced to closet their talent in utter frustration with all the other unappreciated artists, writers and dancers etc. Certainly much modern art I don’t ‘get’, same with modern dance which seems to have moved into physical theatre and I pine for ‘old fashioned modern dance’ but can rarely find it. This may say more about us than the artists, the Impressionists were reviled in their own time also??? Very much enjoyed this episode, thanks.

Hi Trixie: Guess, as they say, it’s all in the eye of the beholder. And if we all liked the same thing, it would be pretty boring. So glad you enjoyed my story!

I have long debated when graffiti, which I once likened to a dog marking its territory, becomes ‘street art’ … this is definitely street art. We could, however, spend an entertaining evening discussing it! My guidelines … by no means hard and fast are … if I can understand it, it’s street art; if I can’t, it’s graffiti. I’m still arguing with myself whether or not stuff commissioned/sanctioned by the authorities, which, in my view, lacks a bit of the spontaneity of the ‘real stuff’ counts.

Hi Keith: I was thinking about your comment as I walked around Bratislava, Slovakia yesterday. I really liked what you said about it being art if you can understand it. I just don’t “get” the tagging with letters that are so stylized that I can’t even read them. To me, they’re just gang markings, though I suspect that’s less so in Europe than in the U.S. However it is also true that there are lots of contemporary art, both paintings and sculpture, that I don;t understand, but I DO like it. Like you said, it’s not a “hard and fast” rule. I equate it to something I heard at a writer’s conference once. Someone asked for a definition of literary writing. The panelists all agreed that they couldn’t put a definition to it, but they all recognized it when they read it. I think street art is a lot like that.

Hi Barb,

Nice article, that’s all I wanted to say!

Take care,

Nate.

Thanks Nate 🙂